Brilliance All Around: Yale Center for British Art

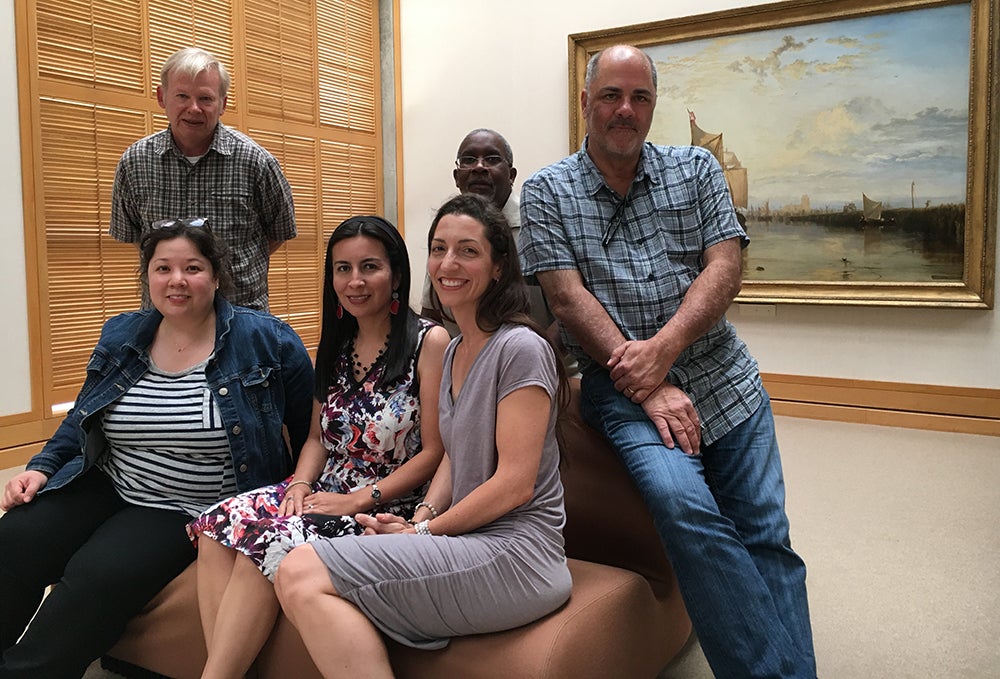

The Center’s Imaging and Intellectual Property team (clockwise from upper left): Richard Caspole, Bernie Staggers, Robert Hixon, Melissa Gold Fournier, Maria Singer, and Anna Bozzuto

The Yale Center for British Art holds the largest collection of British art outside of the United Kingdom.

The Center’s Imaging and Intellectual Property team embarked on a digitizing initiative seven years ago, taking high-definition photos of British art from as early as the Tudor Period (1485 to 1603, England and Wales)—all with the goal of opening access to as much of the museum’s collections as possible.

Museum photographer, Bernie Staggers, was one of 65 staff members who recently shared, in an It’s Your Yale questionnaire, the brilliant contributions that he and his team make to support Yale’s mission. The questionnaire was a part of the Brilliance All Around theme of Staff Appreciation Day 2018.

Bernie said that the brilliance in his department comes from, “Digitizing our collection of British artwork dating back to the 15th century and sharing it with the world via the World Wide Web.”

He noted that his department color-corrects photos so that they look exactly like the piece of art they are capturing, and then puts them online where they are available to be seen, and in most cases, downloaded.

Viewers can have unlimited access to these photos on the Center’s website by doing a simple search of a name or object, like “dog”, “boat” or “cat”. The images that result from the search could range from paintings, to prints, to drawings, to sculpture.

In 2011, Yale’s museums were among the first to offer their images in the public domain and for anyone to use free of charge. According to Melissa Fournier, program manager of West Campus Initiatives and head of Imaging and Intellectual Property, this became a big driver behind the museum’s move to digitization.

“It’s a way for people who can’t make it to the Center to learn about our collections and about art,” Melissa said.

The museum’s commitment to open access enables the study and scholarship of objects within its collections and allows everyone from an elementary school student to a grad student working on a doctorate thesis to view their resources. The Imaging and Intellectual Property team also works with requests from the public and scholars from near and wide, who are often surprised they can receive this information for free.

“What distinguishes what we do here in the studio from other photography labs, other digital photography,” Melissa explained, “is really the fidelity and care that we put into what we do.”

Although the team’s priority is to ensure accuracy of all its photos, in terms of tone and texture, the museum’s photographers also have to be creative with photo techniques, providing photo options with various angles while considering the fragility of the objects.

Photographer Bob Hixon, who has been working in the Center’s Imaging department since March, noted that what the museum does distinguishes them from other collections, valuing as they do the photo production as much as the collection itself.

Richard Caspole, the senior photographer at the museum, described their work as a balance of creativity, science and control.

The photographers utilize technologies like infrared light photography and Reflectance Transformation Imaging software, which allow them to see different layers of paint or drawing that might not be visible to the naked eye. The images they produce are high-definition, and can be blown up beyond 100 percent, even capturing the fibers of paper. These techniques help conservators solve mysteries about a work of art and can help determine previously unknown artists.

When the team first started digitizing, it only had a few hundred images. Now, the number is approaching 210,000, according to Melissa. The team’s goal is to digitize objects once, but one object can have several photos associated with it, like a 1785 book on fencing from the Center’s rare books and manuscripts collection, which Richard is currently working on. He has begun photographing the book from front to back.

“There’s a value to that,” Richard said. “In the future somebody anywhere in the world can look at this, turn it page by page and study it, research it. That itself preserves [over] handling and promotes [its] long-term survival.”

Bernie believes this is a major reason he feels so connected to what he does.

“I’m looking at these images, that if I wasn’t here, I would probably otherwise never see,” he said. “When you have something in your hand and you’re looking at it and it’s a tangible piece of art, you get a peek into the past, understanding our history and England’s history. It’s like you’re a part of history.”

Richard considers what they do is especially important in a time where art and historical objects are being intentionally destroyed around the world.

“I think ultimately,” Richard said, “We’re taking care of our collections, that kind of makes us caretakers for the future.”

Melanie Espinal, New Haven Promise Intern, 2018; writer and photographer